There appears to be a dialectic in the relationship between the tenets of Buddhism and the Psychodynamic Psychotherapy experience. But is there really?

Fundamental to Buddhist philosophy is the concept of non-self, that is, there is no permanent, unchanging entity that constitutes a self, there is no definitive essence of self. Yet in Psychodynamic Psychotherapy, we expend a great deal of time and energy exploring the Self, identifying the circumstances and events that formed our idea of Self and that define Self. Westerners struggle to know Self, and we suffer when we don’t. In the West, we are very much wedded to definitive experiences and knowledge; we love to be sure of things, and we feel we can only be sure of things that are quantifiable through our five senses. Once we know something, we lock it in. It becomes definitive. Isn’t that way of thinking and living antithetical to another fundamental tenet of Buddhism: non-grasping? Buddhism suggests to us that grasping, clinging, is precisely what causes us to suffer. So, how can Buddhist philosophy and Western Psychodynamic Psychotherapy co-exist, complement each other, even support each other? Or are they mutually exclusive? In fact, they can indeed dovetail elegantly.

Exploring the things that have shaped our identity and understanding the meanings we have ascribed to those things and, by extension, to our interpretation of who we are in the world, are not inherently problematic. Where we find ourselves in a world of hurt is in our inflexible attachment to and relentless identification with those things. Our death grip on our personal history is the reason for our suffering simply because, in identifying signal moments in our lives and making them definitive, we ossify them for all time and do not allow for the inevitability of change, for the undeniable evolution of everything. Nothing stays the same. Nothing. When we do not remember that, we also do not allow for how we have evolved, for the “more” that we have become since the time of a formative historic event, and we do not allow for the changes in our relationship with that event and, ultimately, in our relationship with ourself. While something was a certain way or a certain thing at one time, it is not that way or thing today, and our relationship to it must adapt to how it has changed. We are in trouble when we do not adapt: that was then and this is now. Yes, get to know and understand the events of your life; just do not overly identify with or attach to them.

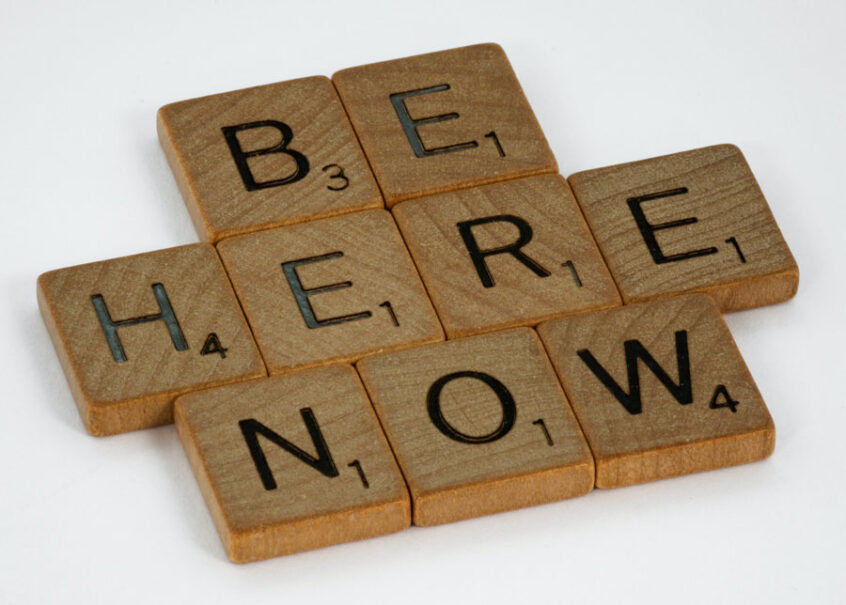

Easier said than done? Perhaps. But here is something to think about when trying to mine the past without getting stuck in it: the past, like the future, is not real. The past is over, it’s done, and it is not happening. Likewise, the future has not happened yet; it too is not happening. It is not real. What gives the past and the future the sense of being real are the feelings we have about them. Like everything else, feelings evolve, and as they evolve, they can become more of what they are, including more powerful. The feelings we develop, for example, about a depressed mother who was emotionally unavailable when we were young tend to increase and intensify the more we grasp onto that experience and the more we recollect that experience – the more we invest in and give life to that experience. That experience, though, is over; all that exists about it today are the feelings we have about it. We are not in a present experience of that relationship with our mother. And here is where mindfulness can be a powerful resource. Mindfulness is simply the awareness of and focus on the here and now, on what is actually happening in the present. Of course, the present is unmeasurably small because it is instantaneously over and done with, consigned to the past. One might extrapolate from that that the present is eternal, that the present is ever present, that there is no past or future. Yet we have learned to perceive past and future, to create these temporal separations – at our own peril, because it is in the